Flight to quality & The Big Lie

Why fitness centers and cappuccino bars are not what's missing from American offices

As I shared a few weeks back, one of the goals of this blog is to help us crack one of the biggest questions of the day plaguing white-collar executives, managers, individual contributors, and most certainly, real estate professionals:

The pandemic slowly becoming a memory of the past, where and how will knowledge work get done in the future?

Of course, there is no concrete answer to this question. While most are asking where will work get done, we've got no crystal ball, and frankly, it's a lot more interesting to focus on a more normative question, which is where work should get done.

But before we can embark on that journey to understand the future of work & the physical world, we'll need to brush aside some of our biases -- that is, what we think we know -- to start with a clean slate.

The office as a resort

The natural place for us to start will be the office of today. Or at least, the office of February 2020.

Once a destitute grid of cubicles, Big Tech arrived in the early 2000s and, desperate to attract skilled talent from a labor pool still far too small, said 'to hell with it'. And so arrived the modern office: wide open floor plans, awe-inducing, gorgeous designs, and playground after playground of amenities. We're talking Michelin-star-quality food, luxury gyms, all-inclusive dry cleaning, first class bus transportation. You name it, they provided it -- the office all of a sudden became a resort.

If you ask most real estate professionals today what the future of the office looks like, you'll hear a similar answer: a mass adoption of what was once niche-tech. The "flight to quality" means a rapid acceleration of the amenitization of the office.

Most office developers today will tell your their market outlook looks something like this: Recently built or renovated Class A buildings with incredible perks in bustling neighborhoods will come out of the pandemic just fine -- better than fine, thriving.

This is a natural, logical perspective on the future of the office. Why? Because just like Big Tech amenitized to woo their recruits to choose them over competitors, today white-collar America needs to woo its workforce back into the office (that is, assuming you believe there is a need for in-person work, which we'll get to in a later post).

With a labor market this hot, force your employees too hard and they will simply quit (or, quiet quit, perhaps I should say).

This tug between employer and employee all stems from the fact that, because of the pandemic, white collar employees have experienced and become accustomed to a workplace benefit that, it turns out, means a whole to them. That is: life without a commute.

There is a cost to the employee of going into the office: the time and money it takes to get there. The average American commuter spends nearly an hour a day on the roads. That's almost 5 hours a week on top of work time that could be spent with family, out on the town, binging another Netflix series.

5 hours a week is a lot of time: enough to save a marriage, stay physically healthy, or be a good parent.

And it’s not just 5 hours. It’s the flexibility that comes with no commute: the ability to pick up your kids from school, go to the dentist, move things around because you’re physically at home.

If we are going to envision a future of physical space, we cannot neglect the cost of the commute: it is real, it is significant, and it must be either reduced or made worthwhile.

And so, back to this "flight to quality."

Fancy Class A buildings are actually still leasing today. In most cities, even San Francisco, tenants in nice buildings are still paying rent.

Many read into this fact as THE answer to the future of the office: that is, to motivate employees back into the office, you simply need a nice space. The way to overcome this employee commute cost is to give employees incredible amenities — laundry service, day care, a full-service gym, you name it. And indeed, developers are pouring money into upscale designs and treats galore.

The problem with lease data

If you just looked at this fact — lease vacancy rates of high-amenity, class A buildings, you would think we have fully recovered from the pandemic. By and large these buildings are leasing at close to the same rates as they did before 2020.

And so, ask a developer: what does the office of 2030 look like? Many would say, luxury buildings are the answer.

But lease data is a lagging indicator. Most companies are holding on to their leases right now because there is a risk to letting go — in the off-chance this whole hybrid thing is a fluke, Elon is right and the world returns to fully in-person work, prematurely letting go of space would have been a massive, costly mistake.

And if you’re in charge of real estate for a big company, your job is to simply not screw up. Spend a bit more than needed to mitigate risk — that’s okay. But bold bets: that’s the CEO’s job, not yours.

Today, an extraordinary number of office tenants have negotiated with their landlords for 1-year lease extensions (instead of re-signing another 5-7 years), hoping that next year they might have a better idea of what’s to come.

In a typical year, something like 15% of American office leases might turnover. According to one analyst we interviewed, because of these 1-year lease extensions, that number might be closer to 25-30% in 2023.

A storm is brewing, and if you look at the wrong numbers, you might miss it.

Who’s actually going in to the office?

Instead of looking at lease data today, we should be looking upstream — what do office tenants actually demand?

The first place to look is occupancy data. If people are continually not showing up to the office, eventually those leases will catch up.

And so, while lease data may tell you the future of the office is the luxury mansion, occupancy data tells you a very different story.

Employees might be coming back into these buildings slightly more than others, but in most markets, by no means are they flocking back. In fact, on a dollar-spent-per-employee-coming-in basis, one could argue these buildings are worse than the alternatives: tons of money, insignificant results.

According to data from Kastle Systems, a company that provides office building key cards, daily average occupancy of office space in the U.S. is between 33% (on Mondays and Fridays, generally) and 56% (on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Thursday) of pre-pandemic norms.

The more stark takeaway is that these figures have barely moved an inch over the past year. With the pandemic now receding in our memories, offices still sit just half as full as they did before 2020, and barely more than they did one year ago today.

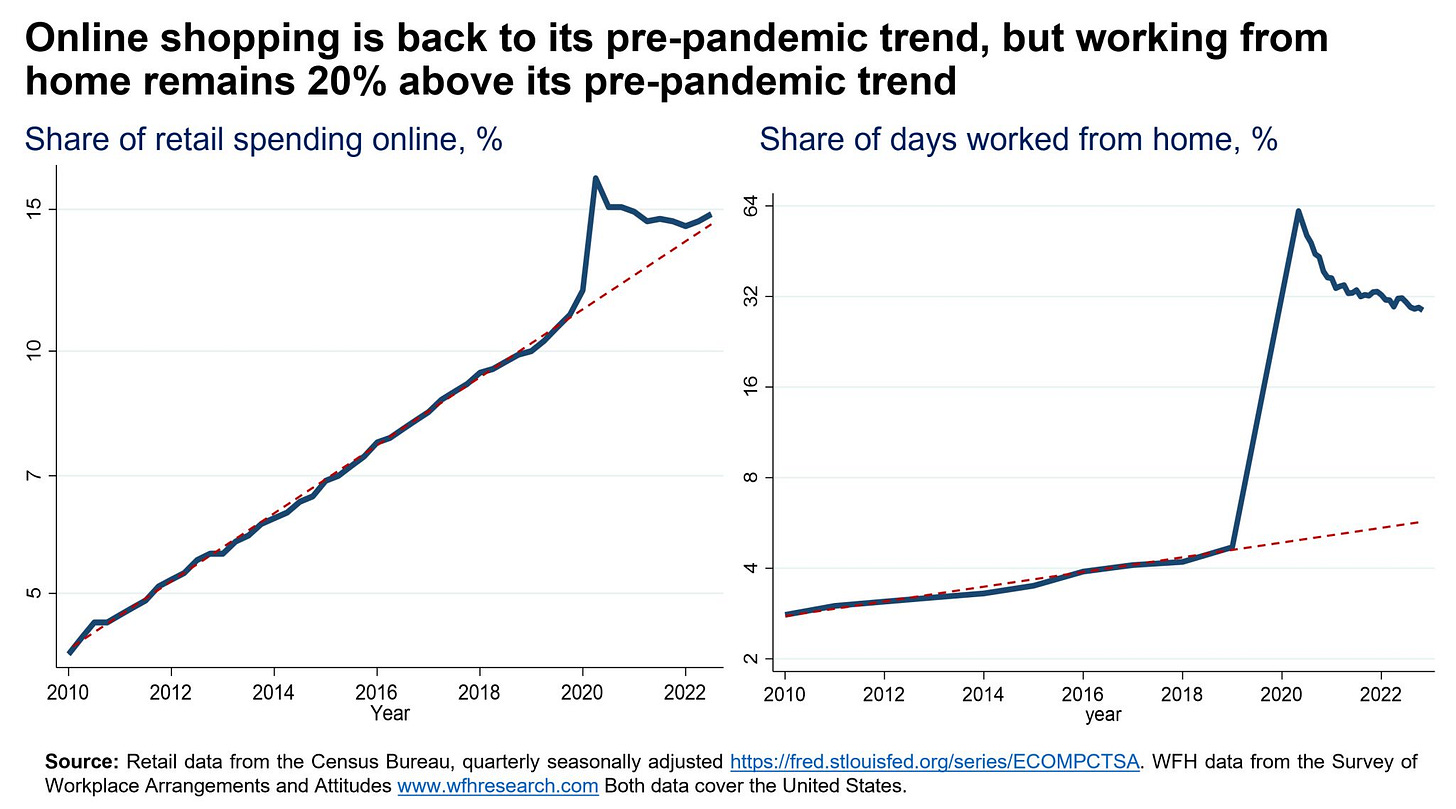

By nearly every other measure of "pre-pandemic normalcy" -- travel, eating out, shopping, schooling -- our country has largely returned to doing business the way we did before 2020. Of course there have been some changes; we buy slightly more online than we used to, for example. But changes have been marginal and expected; by and large things have largely returned to how they used to be.

But not offices.

Amenities are not the answer

Just look at Big Tech. Most mornings I run along the Bay Trail in Menlo Park, past the 57-acre Meta campus fit with a literal redwood forest. The company spent nearly a billion dollars on it, with the project completed just in time for the…. pandemic. Now, they're looking to shed off some of their properties because they're tight on cash and, more importantly, their offices are "lifeless.”

With their head start, Big Tech firms are years ahead on the race to turn the office into a resort. They could not possibly have nicer buildings with more perks and amenities. And yet, Bay Area office occupancy sits lower than most other regions — barely hitting 40% of pre-pandemic occupancy.

When Tim Cook announced a return-to-office for Apple employees last fall, employees informally unionized under the hashtag #AppleTogether to fight back:

I believe this all goes back to the commute. The value of those 5 hours a week, and the flexibility that comes with them, is so significant that no gym or coffee bar could outdo it.

In a piece on Google’s back-to-office plans, NYT architectural and design writer Allison Arieff put it well:

“Work-life balance is not eating three meals a day at your office, going to the gym there, having all your errands done there. Ultimately, people want flexibility and autonomy and the more that Google takes that away, the harder it is going to be.”

The lease-occupancy disconnect

So we are left with a bit of a conundrum: leasing data telling you one story, occupancy a very different one.

This suggests we are in a transition period.

If you assume as I do (and will later make the case for) that in-person work will return to some meaningful degree more than it has already — likely between 2 and 4 days a week — then at least one of the following must be true:

Employers today do not know what they want / need to get their employees back.

The market today does not offer what employers say they need.

I believe both to be true.

And those truths are opportunities: opportunities to start from scratch with a blank slate, to build a new future of work. One that prizes quality time over free lunch, flexibility over top-notch fitness centers.

A future I look to: one where our working population can produce higher quality output, in less time, with more joy.

But that future will not arrive out of the sky. We must craft it intentionally.

More to come ☝️

Sources: