Why 'where' matters

How our physical environment changes how we create -- and why we all should care

This is the first of a two-part essay. Read the second here.

The pandemic slowly becoming a memory of the past, where and how will knowledge work get done in the future?

Over the past few weeks I've broken down the predominant answer to this question -- the idea that perks and amenities will pull people back into the office (the carrot) while a recession might push people back (the stick). We talked about why I think this story is wrong, and why the future of where work gets done will not be a simple mix of office-from-the-past and WFH-of-the-present.

So what does the more nuanced story look like?

The more nuanced story is that work will, over time, get done where it's done best.

It sounds basic, but within this statement is an embedded assumption that many today would not admit to believing: that where you do your work actually matters. That is, if you can do everything your job requires behind a laptop, does it really matter where you're physically sitting?

Flexibility, at what cost?

There's the obvious practical answer to this question, which is that you need decent WiFi, to be on a similar time zone as your coworkers, a little screen privacy (maybe), and perhaps a dual monitor. That would rule out most coffee shops but still leave you with an abundance of flexibility. Flexibility we hold up today as king above all else, king because it delivers us time. Flexibility gives us shortened commutes, long weekends to travel, home cooked meals whenever we want them.

And so, through increased flexibility, the past few years have shown us what more we can get out of our non-work lives when we shift where we work. What we haven't fully explored is what impact a change of working location has on our work itself -- both what we are able to create, and how our work adds meaning to our lives. In other words, what are we trading for that flexibility?

The answer I believe will emerge over time is far more significant and gives meaning to this whole topic to begin with: that where we work has a huge impact on what we produce and how we feel producing it.

Moreover, where we work has dollars-and-cents implications for an organization, and therefore it is dangerous to take workplace flexibility to simply mean "work wherever you want, wherever you want, as long as you get it done." And that’s the problem with "flexibility as king.”

In many ways, we have obsessed so much with optimizing time that we’ve forgotten about space.

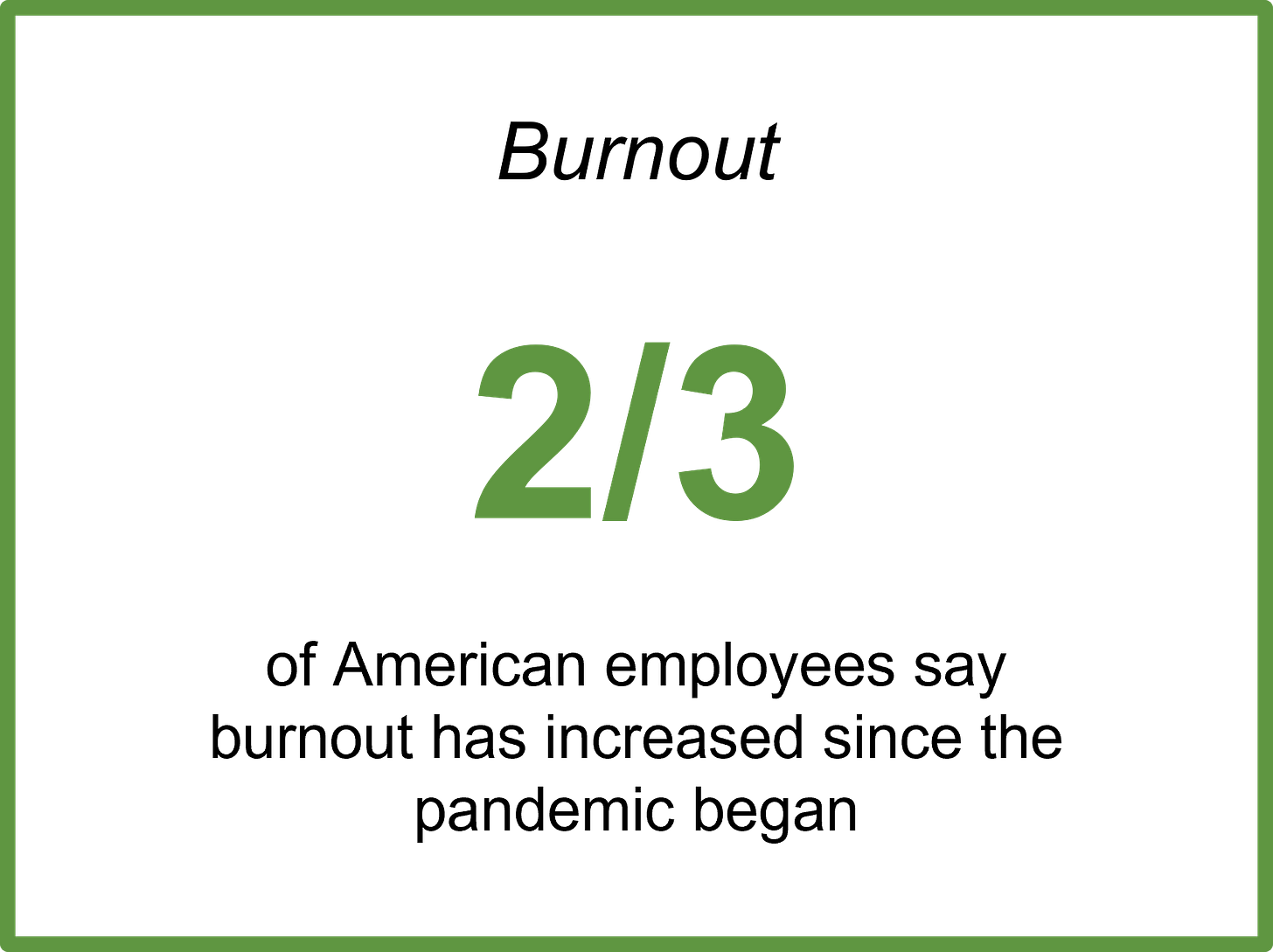

The default home office setup is not conducive to many (not all) types of 'creative work' (which we will define shortly). While at most frustrating in the moment, over time the impact of this environment-intent misalignment is burnout: lack of motivation, productivity loss, resignation.

Why where matters: 2 answers

Two statistics that have piqued my interest in the last year:

An ideation session held in-person will generate, on average, 15-20% more ideas than one held on Zoom, and those ideas will receive higher ratings for originality (Nature).

Two-thirds of remote workers (vs 20% of in-office workers) say they haven’t made a single friend at their company (JobSage survey). This is despite the fact that workplace relationships rank #1 in explaining variation in job satisfaction (HBR) — a key indicator of retention.

The first stat is about what we produce, that is, productivity -- that we actually can produce more of some things (here, ideas) when we are physically together.

The second stat is about how we feel when producing things -- that we might feel better in some places over others, and that that feeling may change how we relate to others around us.

The two stats here are singular grains of data, part of a much larger and still quite emerging body of social psychology that argue the environment we put ourselves in changes how we think and how we act. Both stats tell us: yes, where we work matters a lot. And both make me wonder: what else about where we work have we yet to uncover?

Defining creativity

Whatever your career, there has likely come a point in your work where you have felt 'stuck' -- writer's block, lack of motivation, procrastination. And perhaps in that moment you changed your physical environment, which may have helped you get 'unstuck.’

You went on a walk, put some light music on, moved to a café.

Without going into too much of a neuroscience rabbit hole, I'm going to make the case for why changing the environment changes how your mind works.

As a species we are far from understanding how our brains fully operate, but we do know that of the thousands of decisions we each get to make every day, very few of them are made consciously. When walking, we do not lay out all the options for where we could put down our foot next and decide logically which would make the make sense. We do it instinctively, as we do most things. We have evolved to do this because instinctual decision making is faster and easier, requiring only a fraction of the brainpower and energy as conscious thought.

The same is true for thought work. We can lay out the high-level structure for how we are going to write an email, type a block of code, build a spreadsheet or design a marketing asset. But at some point the words and actions just have to flow.

We have a sense of what it is we want to produce -- the tone we want to strike, the message we want to send, the product we want to output. But the path from step 1 to desired outcome does not run entirely through the rational, aware mind. There's something else that goes on in there that turns ideas into reality. For simplicity's sake let's call it creativity.

Creativity, I believe, is the part of the brain we do not yet understand -- how it is, for example, that we can have a "feel" for what it is we want to say, and all of a sudden a word comes to mind, brilliantly capturing the feeling in an external manifestation that others can understand. That word appears almost out of nowhere; we do not have the awareness to watch as our brains index their libraries, traversing millions of bits of memory, for the right choice. It just happens — in fact, the harder you try to make it happen, the less likely it is to come (the explanatory factor, I believe, behind my mother’s purported wordfinding deficiency, which she attributes to aging).

Under this definition, most knowledge work is or is becoming highly creative. If you don't believe me and think your work is purely a matter of logic, you're probably selling your skills short.

How creativity shows up at work

Here’s a thought experiment for you:

Think about the last discrete piece of "work" you did (e.g., an email you wrote), and imagine you were to write out an instruction sheet of (1) what triggered the need for this piece of work, (2) what outcome you hope to achieve with it, and (3) all the steps to get from need to outcome. The instruction guide can include any level of detail or specificity, but it cannot include any parts of the outcome itself (i.e., it can say "the email should be direct but strike a sensitive tone" but cannot say what words would effectively do this).

For some tasks -- call them, Type 1 -- you would not have a hard time writing this out and giving it to a complete stranger to execute. You might say, for example: "When a customer emails asking for help with the product, send them a friendly reply with a link to our online user manual." You could give the guide to said stranger and trust fully that you'd get the outcome you want at the standard you want.

For other tasks -- call then, Type 2 -- you might find writing this instruction guide to be quite difficult. For example, what if the type of reply you'd want to give to this email would vary by customer, and the tone you would want to strike would depend on the current state of the relationship with that customer and your knowledge of their internal company needs? In this case, any logical instruction guide you could come up with, no matter how detailed, would likely fall short of your ideal. You have a knowledge within that can't easily be taken out.

Type 1 tasks are an inefficient use of our time and, as much as possible, should be handed to computers to do for us. Heck, they will be handed to computers for computers can do them faster and cheaper. And if all the work you do falls into this category, you should be concerned about your job security, because over time, Type 1 tasks will make up a lesser and lesser share of the work that knowledge workers do.

Type 2 tasks are creative pieces of work, the work we do where we are most valuable. It is for these tasks that we are paid a premium above minimum wage -- we have a unique creative ability to execute in ways others might not. Our skill in Type 2 tasks cannot be easily transferred to someone else.

Making the magic happen

The question then becomes: when executing Type 2 tasks, what's going on in our brains to make this creativity happen and how can we help it improve -- better output, in less time, done more enjoyably?

These creative tasks require skill that we accumulate over long periods of time and are able to activate on a moment's notice using our instincts. A sales rep can see where they need to steer the conversation next just as a doctor can recommend a treatment, a sculptor can plant their next carve, or a pro tennis player can change their grip.

We do not know exactly what triggers these instincts, but we do know there are things we can do to help our brains “do creativity” better. We know because we have all felt more creative some days over others. At the extreme end, many of us are familiar with the feeling of entering a 'flow state,' which psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi first defined as “a state in which people are so involved in an activity that nothing else seems to matter.”

In that flow state, we are not marginally better. We are many times better. We produce incredibly fast with such levity that we wonder how it is on other days we can struggle to get a single email out.

Sleep, exercise, healthy food -- there is strong evidence that all of these have a measurable effect on our cognition and creative abilities.

Indeed, the environment around us also has an impact on our brain state -- affecting how aware, focused, creative, or controlled we are at any given moment. This isn’t a new discovery — but perhaps one we’ve forgotten a little bit these past few years.

The importance of the environment on our brain and how it shows up cannot be overstated. It's the reason why:

Churches and other prayer sites have for thousands of years been built around grandiose, opulent sanctuaries that are believed to inspire awe and make it easier for people to pray

Restaurants and cafés are generally designed with ambient lighting, intended to make it easier to relax and socialize with others

Office buildings have been known to set thermostats slightly below room temperature as it is believed that people are able to focus better when slightly cold

In fact, our environment can even affect our long term mental health. A study I recently came across showed that the simple sound of birds chirping could reduce a person's chances of experiencing severe depression (NPR).

When it comes to work, environment matters. The lighting, the sound, the presence of people around us -- these factors and more all have an impact on how we are able to create.

And, more interestingly, the enablers of maximum brain creativity are not the same for all tasks. Picture yourself having to:

Design a long-term strategic plan for your organization, including the mission, vision and values

Identify the KPIs and performance metrics you want to use to support a new product launch

Deliver tough news to a colleague about their underperformance

Each of these tasks requires completely different learned skills, relying on instincts activated by different triggers and optimized under different environments.

One of the space designers we interviewed last fall opened my eyes to what space can do for you:

“The ambient sound of others talking around you makes you feel safe — independent but supported. The height of the back of your chair makes you feel protected and therefore confident. The photos of your team on the wall make you feel included. All these things affect how you produce.”

Are you seeing the problem here?

Our computers, turbo-loaded with productivity and execution tools galore, are far from being able to change the environment we experience. Three years into the pandemic, we've all experienced the misalignment of environment and intent.

We've been deep in flow, only to be thrown off by an "urgent" Slack message or email. We've facilitated workshops or given presentations on Zoom, awkwardly waiting for our participants to engage with us the way we'd expect them to in person. We've opened up with our bosses about our frustrations and discontents, listening carefully to their response and hearing all the right words -- but not truly feeling the empathy we so desire.

These experiences are frustrating in the moment. Over time, they build up, eating away at our motivation and drive to bring our best selves to the job. We produce less and check out more. The Great Resignation did not happen because of this environment-intent misalignment, but it surely played a role.

We are brilliant creatures, creating art in all aspects of the sense.

But we must not forget: where we work matters. It matters to the individual and most certainly to the firm. It changes what we create and how we feel. And for that, all of us should be investing more in understanding and building around this need.

Brilliant. Lots to unpack here. May I suggest conducting an interview for one of your next posts?

Great read! Love your takes on this topic - keep the posts rolling : )